Article Copied from the American Rhododendron Society Blog

Print date: 9/4/2025

The Search For Gold -

A Lifetime of Organic Artistry

2 September 2012 @ 19:32 | Posted by Emily Weissman

To craft something "better" has always been man's aim. Horticulturalists have, throughout time, taken this to heart as the attempt to combine beauty and form, sculpting nature to create the previously impossible. Around 1968, rhododendron hybridizers were faced with a challenge to not simply combine species, but to give life to something that had never before existed in nature: the golden rhododendron.

"There was a breakthrough in yellows…" says Frank Fujioka to me as we sit in the warm light of his kitchen, sun setting on the beautiful view of Puget Sound out his bay windows. “…Everyone had to work for yellows, and we didn’t think much about what the plant looks like. Some…were really sprawled ugly things, but if you had yellow, wow! That was what was really important."

Fujioka continues on to explain that the closer a rhododendron was to deep, pure daffodil yellow, the better. Many hybridizers simply combined white flowers with cream in hopes of drawing out the elusive shade, a system which Fujioka himself employed in the beginning days. "You get tired of getting poor results!" he confided in me, "so you think, there must be a better way". Thus, a more scientific approach was discussed. "You achieve your goals faster, I think, if you studied the genetics." You can't just combine this with that and hope for a miracle. "Sometimes you get pink!"

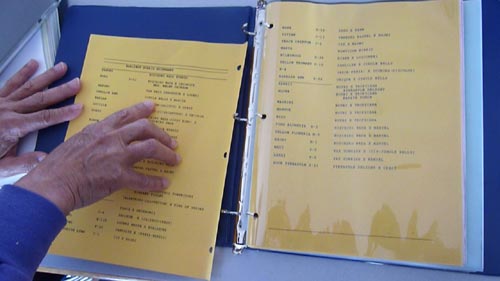

When asked if he recorded all of the genetic data by hand, Fujioka laughed. "No… just the names of the parents," he told me, flipping through page after page of meticulously typed and hand written records in a binder. You first consider that "this parent used this species" and then you follow through many generations, studying it. "That became the fun part," he quipped with a revealing grin. The binder Fujioka shared with me listed hundreds of "nicknames" for crosses that he had created and were still in the testing stage. These nicknames were not to become the final registered titles of plants, but instead held a personal flair, ranging from Hawaiian Islands to family members. "Waikiki" and "Clarice" served only to keep complicated multi-generational hybrids straight. When I questioned Fujioka as to what percent of his experiments had become registered hybrids, his answer was a astonishing “not many.” I listened, impressed, as he explained to me his demanding process for testing all of his hybrids before submitting them to the registry. “[I] feel that if there is going to be a plant floating around… then the homeowner who buys that plant should be able to succeed…if this spring I come out with a plant I really like, I’ll …grow them out in the field. There it is exposed to full sun and minimal care, and I’ll evaluate how well they do. I’ll also dig them up to see what kind of root structure they have because that’s the key to a good plant.” This time-consuming method was not just for Fujioka’s benefit however; he also implied that it was in the best interest of the society. If a new grower attempts “to grow [a rhodie] and it dies…pretty soon you’re saying ‘oh, rhodos are no good.’ So it’s not good for our reputation.”

Beyond the complicated genetic tracing, growing new varieties of rhododendrons is no easy task, and certainly not one for those interested in instant gratification. “It’s a long process,” said Fujioka about hybridizing. Often he spends up to six years growing a plant that is simply one more step in the direction of his end goal. More often than not however, he has a strategic plan. “Sometimes you’re thinking three generations ahead,” he tells me. This was certainly the case in his work towards the ground-breaking discovery of a golden rhododendron. For Fujioka, resounding success came after many years in the form of a stunning bloom called ‘Seaview Sunset’ who’s beautiful coloring seems to “glow” in certain lighting. The popularity of this hybrid, registered in 1988, has increased exponentially, and has become a favorite in the Northwest and beyond.

But Fujioka shared with me that he hadn’t always been so scientific in his approach. As a child his only gardening experience had been pulling out his mother’s carrot plants and shoving back any that were too small, in fruitless hope they might continue growing. Later as a high school psychologist in Edmonds, Washington, he found his interest in gardening blossomed from practicality after purchasing his first home. “It was a small little old house, but it just didn’t have anything. Just green grass, that’s all it was.” So off he went to the nearest nursery, and asked for some plants to fill the empty space. What caught his eye, of course, were the laden blooms of the brightly colored rhododendrons. Disappointed by the fact that there were no, in particular, red rhodies for sale, Fujioka asked the nurseryman for recommendations and went off on a quest. He described in detail his impressions after entering one specific nursery; “I went in there and (this was in the spring) it was like magic. There were acres and acres of these big plants full of flowers…and then the old man came out.” This ‘old man’ he would later discover to be Halfdan Lem, one of the premiere pioneer rhododendron hybridizers in the Northwest, and a true friend. Back in his kitchen, Fujioka’s smile widened as he told of asking Lem for ‘The Honourable Jean Marie De Montague’, the most generic red rhododendron, and being refused. “He said to me…‘I have finer things.’”

Halfdan Lem was only the first of many inspirational and lasting friendships Fujioka made through his love of horticulture, many of which took root through his association with the American Rhododendron Society. Fujioka shared with me that although he had originally joined the Society to learn (there was a dearth of accurate rhododendron information at the time), he instantly found that that ‘plants people’ were some of the nicest you’d meet. I could barely keep from crying from laughter as he animatedly described an experience that illustrated a community as unique and wonderful as the plants they propagated… “One of the most fascinating things to me was how uninhibited everyone was in terms of enjoying what we were enjoying. I wish I had a camera at that time! There were three hefty guys, kind of fat, you know? And there were two of them talking, and a third one appears…with a rose! He said, “look at this! Smell this!” So here are three hefty guys sniffing a rose. That’s the kind of people I like, just comfortable with themselves. That made a big impression on me. I thought, “ok, that’s it. These are the kind of people I want to hang around with.”

Although Fujioka’s race to hybridize a golden rhododendron is now long over, the excitement of producing an original creation is still very much alive. This excitement is what he longs to share with the next generation. “I keep looking for young people to recruit so we can pass on our information, but there aren’t many...I think they’re too busy doing other things. So horticulture in general is suffering because we’re not able to get young people interested in horticulture. Maybe they’ll get tired of whatever they prefer doing and decide that working with dirt is more fun, more fulfilling.” Fujioka suggests what we must tap into is the part of ourselves that loves to create. He tells me of the artistry of gardening and relates it to classic painters and sculptors. While strolling slowly through his garden later, he points out the importance of the variation of greenery in a garden layout, relating it to the artistic movement monochromatism. “We have within us this innate creativity, but many of us were never allowed or encouraged to explore it…so I try to look for that in young people and if I sense that they have that, then I go from there…You know, you don’t need a magic wand!”

Despite being a true artist, friend to many, innovator, and one of the most influential hybridizers of his time, Fujioka has a surprising answer when I ask him what he would most like to be remembered for. “That I was a nice guy. You know, to me, that’s the bottom line.”